September 16, 2013

The three last endnotes today.

[23] The golden age of elemental magic is generally considered to have ended nearly a millennium ago with the passing of Leopold Sidorov and Manami Kaneshiro, who spent their careers in a virulent rivalry and died in a duel that killed both, along with a number of unfortunate spectators.

Hundreds of years went by without the next truly great elemental mage coming along. It had become accepted wisdom that another one would never be witnessed when Hesperia the Magnificent came into her powers, one of the greatest among the great.

It rather gives us hope that we might yet see an immensely formidable elemental mage in our lifetime.

—From The Lives and Deeds of Great Elemental Mages

[22] The establishment of a permanent no-vaulting zone require a heavy initial investment of time—it cannot be hurried. The setting up of a temporary no-vaulting zone, however, requires not time, but labor.

A few friends on a camping trip can manage a temporary no-vaulting zone around their tent in about an hour. A few dozen friends can do the same for a small public park, to have themselves a party—provided they first secure the permits, of course. Armies, with their much larger number of mages on hand, have been known to turn small cities into temporary no-vaulting zones overnight.

—From The Art and Science of Magic: A Primer

[21] The wyvern is the rare carnivore that consents to being domesticated. But wyverns born in captivity tend to be slower and less ferocious. This is fine for mages who wish to keep wyverns as pets, but unsatisfactory for mages who race wyverns or those looking for a fierce guard dragon.

Wyverns born and raised in the wild and subsequently tamed are, therefore, far more desirable. It has become the established practice of stable masters to sneak eggs from their prize wyverns into the aeries of feral wyverns, then later track down the juvenile wyverns at a stage just short of maturity to tame and bring back into the fold.

—From The Dragon Watcher’s Field Guide

September 15, 2013

[20] It is difficult to predict how powerful a child elemental mage will become. A toddler elemental mageling who can shift the foundation of a house in a rage may be able to lift no more than a quarter ton block of stone as an adult.

Sometimes the reverse is true. An elemental mage who can move no more than a quarter ton block of stone under normal circumstances may very well manage to lift something twenty times heavier when his or her life depends on it.

—From The Lives and Deeds of Great Elemental Mages

September 14, 2013

[19] As anyone who had read a story of misunderstanding knows, overhearing part of a conversation, without the proper context, can lead to devastatingly mistaken conclusions.

For that reason, among seers, those who see future in long, unbroken stretches are considered far more gifted than those to whom only quick flashes are revealed, as short, chaotic glimpses are much more prone to misinterpretations, if they can be deciphered at all.

Even rarer are seers who can view the same set of future events repeatedly, allow them to notice greater texture and details with each iteration. Such visions become the most unambiguous sign posts along the otherwise unpredictably swerving road that is the forward progress of time.

—From When Will it Rain and How Much: Visions Both Luminous and Ordinary

September 13, 2013

[18] The power of a potent mind mage is often compared to that of a drill, boring through the skull to reach its quarry. But the truth is slightly more complex. In a probe, the mind of a mind mage, though dominant, is in a sense as exposed as the mind of its prey, as vulnerable as it is devastating.

—From The Art and Science of Magic: A Primer

September 12, 2013

[17] The Bane’s public embrace of mind mages marked a watershed event in his ascendance. Until then, mind mages, even those valued as tools of torture and extraction, had always been kept out of the view, not acknowledged and certainly never honored.

But the Bane brought them out in the open and gave them some of the highest offices of his empire. And not just those of Atlantean birth, but mind mages from many realms, in the secure knowledge that their first loyalty would always be to him, who elevated them to positions of trust and distinction, and not to the native realms which had treated them with fear and loathing.

—From A Chronological Survey of the Last Great Rebellion

September 11, 2013

[16] The Coalition for Safer Magic and The League of Sensible Parenting—henceforth referred to as the undersigned—hereby petition the High Council of the Domain to remove all mentions of mage-to-animal transmogrification from textbooks intended for primary and secondary educational establishments.

Each year, dozens of young magelings, piqued by the allusion in these textbooks, attempt such transmogrifications. They concoct dreadful, frequently toxic potions, misapply spells, and cause fires and explosions at home and at school—not to mention harm to their persons.

In this past winter alone, there had been a mageling unable to breathe normally from having grown gills, another turned nearly blind after acquiring bat vision, and a third who lost all his hair by molting. That the cases have been reversible do not mitigate their severity.

—From Petition No. 4391, lodged with the High Council of the Domain 21 April, 1029

September 10, 2013 (One week from release)

[15] It bears remembering that advances in magic do not always follow a linear progression: Some developments commonly regarded as modern are but recent rediscoveries of what had come before. Court physicians for the rulers of Mesopotamia, for example, had formulated entire classes of prophylactic spells. The spells were eventually lost to war, fire, and other ravages of Fortune, but records survived to attest to their miraculous effectiveness.

To consider a more current example, magical historians have argued for years that the venture-book, perhaps the most successful magical application in a generation, is but a commercial adaptation of devices that had been employed for centuries by the House of Elberon to instruct and train its young heirs, especially in times of adversity. Newly unveiled documents concerning the Last Great Rebellion seem to indicate that Prince Titus VII indeed had at his disposal devices that performed many of the functions of present-day venture-books, except better.

—From the article “Everything Old is New Again”, in the Delamer Observer, 2 December

September 9, 2013

[14] It cannot be stressed enough that blood magic is not the same as sacrificial magic. Sacrificial magic, needless to say, has always been taboo in mage realms. Mages who choose to break the taboo usually do so among nonmages, manipulating local religious rituals to suit their own ends.

Blood magic does not require the taking of lives or the severing of body parts. Furthermore, its spells, contrary to popular belief, do not drain the body. Only a very minute amount of blood is needed to power a spell and that blood must come from willing participants. Forcibly spilled blood neither keeps secrets nor binds anyone in oaths.

—From The Art and Science of Magic: A Primer

September 8, 2013

[13] The following is a reproduction of a January Uprising-era underground pamphlet.

We have ill news from our friends on the Subcontinent. The offensive in the Hindu Kush has failed catastrophically. Survivors report of Atlantean aerial vehicles of type never before seen, armored and enclosed chariots that repel every known assault spell.

To make matters a hundred times worse, the armored chariots spray a deadly potion in its wake. The potion is clear and odorless. Many of the resistance fighters on the ground first believed it to be natural precipitation and believed the demise of their colleagues to be casualties of battle. But afterwards, when massive civilian deaths were tallied in the armored chariots’ flight paths, our friends had no choice but to conclude that Atlantis had unveiled a terrifying new weapon, death rain.

—From A Chronological Survey of the Last Great Rebellion

September 7, 2013

[12] Last week’s confirmation by the Citadel that Princess Ariadne is indeed expecting her first child ended months of speculation—and raised even more questions.

The decree governing succession to the crown specify only that an inheritor should be a firstborn child of the lineage of Titus the Great. No mention is made of legitimacy.

With a few notable exceptions, most princely bastards have refrained from staking a claim to the throne. But the Observer’s sources believe that Princess Ariadne intends to declare her firstborn an heir of the House of Elberon.

The declaration, should it come, would not be challenged on grounds of legality. But most mages surveyed by the Delamer Observer are of the opinion that they deserve to know the paternity of a future ruling prince or princess. The princess’s steadfast refusal to name the father of her child has damaged her erstwhile pristine reputation. Rumors brew and froth, many casting doubt on both the princess’s character and her fitness to rule.

—From “The Princess’s Hurdle,” The Delamer Observer, 8 June, Year of the Domain 1014

September 6, 2013

[11] Not much will be said of otherwise charms here, given that they are both too advanced for the scope of this book and, more importantly, illegal.

Love philters are often mistakenly pronounced the best known examples of otherwise magic. The effects of love philters, however violent, are temporary. The effects of true otherwise charms, on the other hand, are semi-permanent to permanent. And they seek not to alter emotions and short-term behaviors, but perceived facts. In other words, they are campaigns of misinformation.

Fortunately, it is not easy to implement otherwise spells. If Mr. Stickyfingers is a known thief, no otherwise spell will not change that perception. Nor will otherwise magic help someone already suspected of lying. Otherwise spells are only effective when 1) the intended audience is entirely unwary and 2) the misinformation disseminated does not run counter to established facts.

—From The Art and Science of Magic: A Primer

September 5, 2013

[10] Do you need a wand? The short answer is, no, you do not. The working of a spell requires only intent and action, and it has been conclusively proven that mouthing or speaking the words of a spell constitutes action.

Why then do we still use wands? One reason is heritage: We have wielded wands for so long it seems almost rude to stop. Another is habit: Mages are accustomed and attached to their wands. But more practically, the wand acts as an amplifier. Spells are more powerful and more effective when performed with a wand—reason enough to find one that fits well in your hand.

—From The Art and Science of Magic: A Primer

September 4, 2013

[9] It took more than fifty years after vaulting was first achieved for the general mage population to accept that vaulting is not a universal ability. Until then, it was believed that with earlier and better training, and an ever-burgeoning collection of vaulting aids, every mage could be taught to vault. Nervous parents regularly enrolled children as young as three in vaulting classes, for fear that should the tots start any later, they would grow up to be emus—flightless birds—disdained by their peers. Medical literature of the day recorded multiple instances of dangerously premature labor, brought on by expectant mothers hitching too many vaults in misguided attempts to inculcate the process in the minds of their gestating babies.

But before society at large could accept that vaulting was not possible for every mage, it had to first accept that mages who could vault often did not vault very far. In the heady early years of vaulting, mages were convinced their vaulting range would continue to improve, as long as they continued to practice. When these pioneers began to be thwarted by personal limits, they attributed it to late starts, incorrect training, and a flawed understanding of the principles of vaulting—and encourage the next generation to push harder and more astutely.

The best data currently available suggest that between seventy-five to eighty percent of adult mages are capable of vaulting. Of those, more than ninety percent have a one-time vaulting range of less than fifteen miles. Only a quarter can tolerate consecutive vaults, the rest must wait at least twelve hours between vaults.

Moreover, it is now known that vaulting exacerbates pre-existing medical conditions. Expectant mothers, the infirm, the elderly, and those recovering from serious illness should refrain from vaulting. In rare instances, vaulting has been known to cause grave consequences in otherwise healthy individuals.

—From The Mage’s Household Guide to Health and Wellness

September 3, 2013

[8] A quick word on countersigns before we move on to our first section of spells.

The spells in this and many other textbooks do not have countersigns. But no one ever became archmage using spells that can be found in public libraries. Heirloom spells and cutting edge spells, considered far more powerful, usually operated with an incantation that can be said aloud—and therefore overheard by others—and a countersign that is never uttered, to preserve the secrecy of the spell.

By the same token, countersigns are also sometimes used with passwords, to maximize the latter’s effectiveness and security.

—From The Art and Science of Magic: A Primer

September 2, 2013

[7] Magelings with elemental powers present additional challenges to parents and caregivers, there is no disputing that. Most young children give into temper tantrums at least once in a while. But a toddler elemental mage in a screaming fit is liable to shift a house from its foundation or choke the air from a playmate’s lungs–without ever meaning to. And even when elemental magelings grow older, they might still inadvertently let their powers get the better of them.

In this chapter we aim to present a comprehensive list of training techniques for disrupting the direct connection between an elemental magelings’ anger and his or her instincts to turn to the elements. It has been repeatedly pointed out that violence is hardly the best substitute, but until we learn how to perfectly control small children’s emotions, their tiny fists will remain preferable to their—at times—disproportionally immense powers.

—from The Care and Feeding of Your Elemenal Mageling

September 1, 2013

[6] New Atlantis’s rise as a dominant mage power was, in many ways, a surprising event.

The island, while big—nearly twice the size of the Domain—is ill suited to large-scale civilization. The volcanic frenzy behind its creation was too recent, its interior too steep and angular. Much of the ground is basalt, arduous to walk upon, impossible to cultivate. Sea life, astonishingly abundant when mages first set foot on the island, came dangerously close to irreversible depletion at several points in its eight-hundred-year history.

Two hundred of these eight hundred years, in fact, were known as the Famine Centuries. The isolation of the island, the relative primitiveness of long-distance transportation of the era, and wide-spread corruption among members of the royal clan made aid campaigns mounted by other mage realms largely ineffectual. At the end of the Famine Centuries, population on the island had plunged by at least seventy percent.

The Bane is believed to have been born during the last decade of the Famine Centuries, into a devastated, lawless society. Whether he would have still become the single most influential mage on earth had he come of age in a more prosperous realm, we can only speculate. But there is no doubt that the chaos and deprivations of his youth influenced his desire for order and control throughout his career.

—from Empire: The Rise of New Atlantis

August 31, 2013

[5] Soon after the advent of vaulting, mages realized that this revolutionary new means of travel presented a serious problem to the security of public institutions and private households alike. A mage who has seen the interior of a building can vault back into it any time, which quite defeats the purpose of having walls in the first place.

A series of ingenious—and sometimes laughable—solutions came into being. Who can forget the Nevor-Same™ Home, which changed the colors of a house’s walls and furnishing after every visitor? Randomly, one might add, leading to some of the ugliest interiors ever to assault a mage’s eyes.

Nowadays we enjoy advanced and discreet spells to protect our dwellings from ill-intentioned vaulters. The spells listed in this section, when implemented properly, are guaranteed to repel any unauthorized attempt to vault into your home.*

*None of these spells, singly or in combination, work when a quasi-vaulter is involved. Therefore we are terribly glad that quasi-vaulters have become virtually impossible to find.

—From Advice to the Novice Householder

August 30, 2013

[4] These days, the term “beauty witch” has become quite diluted.

On the one hand, the leading ladies of stage and fashion are sometimes referred to as beauty witches. On the other hand, it has also become an euphemism for prostitutes, much to the annoyance of beauty witches who considered themselves far above such common strumpets.

For the purposes of this book, we shall cleave to the classic definition of beauty witch: a woman of great beauty and elegant taste who is well versed in music, literature, and art and can converse intelligently on most topics under the sun. She may or may not depend economically on the generosity of a protector, but she has no profession other than that of her personal attractions.

—From Sublime Loveliness: The Seven Most Celebrated Beauty Witches of All Time

August 29, 2013

[3] The separation of mage and nonmage populations has never been absolute, on account of vestigial mage communities that either opted not to join a larger mage society or subsequently left.

The nonmages, with their burgeoning advances in science and technology, may someday pose a threat to magekind. But throughout history, the greatest menace to mages has always been other mages. Never was a successful witch-hunt mounted without the cooperation of mages willing to turn on their own. For that reason, mages who dwell among nonmages are subject to the strictest regulation.

The Exiles from the January Uprising presented a curious scenario. By the time revolt had been quelled, there were no other mage realms to which its sympathizers could flee: Atlantis was the master of the entire mage world. So they chose instead to live among nonmages and to plot their return therein.

—From A Chronological Survey of the Last Great Rebellion

August 28, 2013

[2] The Domain’s classification as a principality rather than a kingdom has often confused mages. It is certainly not a micro-realm: At more than one hundred thousand square miles in area, it is one of the largest mage realms on Earth—and historically, one of the most influential.

Legend has it that the night before his coronation, Titus the Great, the unifier of the Domain, had a dream in which a voice cried, “The King is dead and his house fallen.” To avoid that fate, he had himself crowned Master of the Realm, styled His Serene Highness, a prince instead of a king. The ruse worked: He lived to a ripe old age and his house has endured. Today, when most other monarchs and princes are figureheads without actual power, the House of Elberon remains that rare phenomenon among mage realms: a ruling dynasty.

—From The Domain: A Guide to Its History and Customs

August 27, 2013

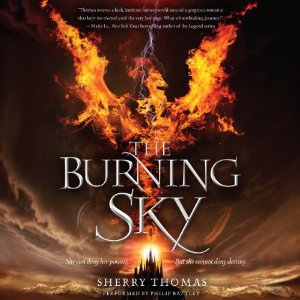

I read Dune at a young and impressionable age. And one of the things I remember very clearly about the book was that each chapter opened with a short excerpt from a fictional history/encyclopedia/etc. That struck me as beyond cool. So any time I have tried my hand at SFF, I have always done the same. And The Burning Sky was, of course, no exception.

But we debated where to put these world-building tidbits. First they were chapter openers, then they became footnotes. In the end, they became endnotes. Because we took so long to come to that decision, the endnotes were not in the advance copies of the book.

So here then is content that is new, even for folks who have read the advance copies.

(I will be adding one endnote to this post every day, until I run out of them. And I will add reference pages once I have final copies in my possession.)

[1] For centuries historians and magical theorists have debated the correlation between the rise of subtle magic and the decline of elemental magic. Were they merely parallel developments or did one cause the other? An agreement may never come, but we do know that the decline has affected not only the number of elemental mages—from approximately three percent of the mage population to less than one percent—but also the power each individual elemental mage wields over the elements.

Presently, quarry workers still regularly lift twenty-ton blocks of stone, the record of the decade being one hundred thirty-five tons by a single mage. But most elemental mages make few uses of their dwindling powers and are capable of little more than parlor tricks. All the more astonishing as we look back upon the great elemental mages of an earlier age, those individuals who set mountains in perpetual motion and destroyed—and created—entire realms.

—From The Lives and Deeds of Great Elemental Mages